Potatoes, just like tomatoes, also flourish in the dry North

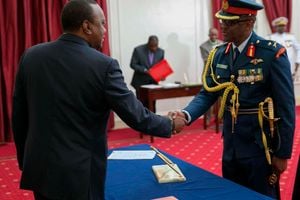

Wajir South sub-county agriculture extension officer, Hussein Ahmed Mohamud leads farmers in planting potatoes in one of the farms in the region. He notes that the county possesses conditions that are conducive for the crops cultivation and just needs sufficient water. PHOTO | COURTESY

What you need to know:

- Residents of the arid Wajir County are embracing horticulture farming, in particular potato cultivation, after a recent trial turned out successful.

- Herweijer notes that contrary to popular belief, potatoes can actually grow almost everywhere in Kenya, as long as there is no frost at night and no extreme heat during the day.

- Wajir’s population is now moving from core pastoralism to more agro-pastoral activities, including planting other crops like sorghum, maize and cereals.

- Skin that is well-set on potatoes helps to prevent it from harvest-damage such as superficial cuts and bruises,” she observes.

Bute is a fertile yet arid region about 200km from Wajir Town, towards the mountainous border area with Ethiopia.

It sits just a few kilometres from Moyale town, and for several years, nomadic livestock-keeping has been the local’s mainstay.

But this is fast-changing as residents embrace horticulture farming, in particular potato cultivation, after a recent trial turned out successful.

“The area around Bute has rich soils for crop cultivation but only lack sufficient water,” says Wajir South sub-county agriculture extension officer, Hussein Ahmed Mohamud.

Mohamud notes Habaswein in Wajir South, through which Ewaso Nyiro River crosses, as well as Wajir Central, which has some oases, have slightly saline soils but are still conducive for crop cultivation, including potato farming.

These soils range from sandy-clay to sandy-loam to pure clay, and with the right farming practices, potatoes do well.

Experts advise that testing such soils before cultivation is key as due to high alkalinity or salinity, there could likely be poor or no germination.

“In Kenya, the perception has been that potatoes only grow well in colder and wetter areas like Meru, Molo and Kinangop.

But shockingly, we tried potato farming in Wajir, one of the hottest and driest counties and it worked?” says Corien Herweijer, the business development manager at Agrico East Africa, a subsidiary of Agrico BV (Netherlands), a global producer of seed potato.

Herweijer notes that contrary to popular belief, potatoes can actually grow almost everywhere in Kenya, as long as there is no frost at night and no extreme heat during the day.

“Water is important though, so one can depend either on rainfall or irrigation. But soil testing is a must, you spend a little on it but it saves you a lot more,” she adds.

ENHANCE FOOD SECURITY

How much water potato needs, according to her, depends a lot on the soil type, temperatures, and variety, as moisture is needed in the soil at planting, at tuber setting, and later during full growth period.

“If you can clump the soil in your hand and if it remains a solid piece, this indicates that it is moist enough. If you clump the soil and have a lot of water draining from your hand, then it is too wet. If you clump and it falls apart, then it is too dry. So through irrigation, you can ideally provide at least 15mm of water per week, depending on soil type,” she advises.

Herweijer notes that Penn State University Food, Energy, and Water (FEW) Nexus programme has successfully been growing leafy vegetables, tomatoes, onions and capsicums under irrigation in the county and felt that other crops could be introduced, thus, approached them.

“Wajir’s population is now moving from core pastoralism to more agro-pastoral activities, including planting other crops like sorghum, maize and cereals,” says Herweijer.

Proud farmer, Omar Haile Abdirahman, displays potatoes that he has just harvested in his farm in Bute, Wajir County. Agro-pastoralism will change the livelihoods of the region’s inhabitants as they acquire new skills to enhance their food security and living. PHOTO | COURTESY

Mohamud explains that normally, the county buys its potatoes from Moyale and Meru, however, with access to enough water and good management, farmers in the county will now be able to produce their own potatoes, especially of the Destiny variety, which has a short maturing period and good heat tolerance, as well as the Manitou variety, which is more resilient to the agro-ecological conditions prevalent in the region.

Wajir agriculture director Jelle Abdi notes that with the advent of potato cultivation in the largely arid region, its inhabitants are now bound to enhance their food security and diets by diversifying produce from their farming activities, as well as improve their livelihoods.

Yussuf Abdi Gedi, who is the Agriculture executive, says agro-pastoralism will change the livelihoods of the region’s inhabitants as they acquire new skills to enhance their living.

READY FOR HARVESTING

Omar Haile Abdirahman, a farmer who took up potato farming in Bute, thought he had lost all his efforts’ worth when he did not observe any flowers forming on his crops, which hitherto appeared robust and had a healthy vegetative stage. His fear was that there was no tuberisation taking place.

However, after seeking experts’ advice, he was told there was no major cause for alarm as not all potato varieties produce flowers.

“Although flowering helps to identify different potato varieties and usually happens at tuber formation stage, no flowers does not necessarily mean no tubers. Farmers are, however, encouraged to try and carefully dig up one of the potatoes at such times when they are supposed to flower, and observe tuber formation,” advises Herweijer.

She adds that the best way to check if potatoes are ready for harvesting is through making sure the foliage has completely dried up and wilted, and then confirming that the stem feeding the tubers into the ground has also dried up.

“Then dig up a plant and do the ‘finger test’ on the tubers. The test involves rubbing the thumb over the skin of the potato. If the skin peels off, the potato is not ready for harvesting and should be left in the soil for another week to harden, before the process is repeated.

Skin that is well-set on potatoes helps to prevent it from harvest-damage such as superficial cuts and bruises,” she observes.

Also, in the last few weeks of growth, the potato has to put on most of its weight as the sugars in the plant come down and are turned into starch.

Harvesting the crop too early essentially means lower quality produce and less than optimal weight.