Kenya’s literature is ailing but our local languages can save it

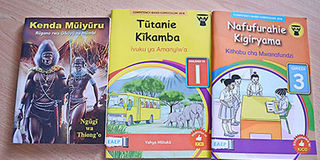

Yahya Mutuku’s Tunanie Kikamba: Ivuku ya Amanyiwa, Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s Kenda Muiyuru: Rugano rwa Gikuyu na Mumbi, and collectively authored Nafufurahie Kigiryam. PHOTO| WILLIAM OERI

What you need to know:

- Except for Ngugi’s, the other books were primarily designated for the current “Competency-Based Curriculum” for schools.

- As we got talking about the dynamics of publishing in mother tongue in Kenya, we revisited the then public debate on the schools’ curriculum review process, and the historical language debate in African literature, about which I shall comment shortly.

Few poems have the punch of Antonio Jacinto’s “Letter to a Contract Worker”, in which the persona laments his inability to express his love and mourn the pain of separation because, “ … oh my love, I cannot understand / why it is, why, why, why it is, my dear / that you cannot read / and I — Oh the hopelessness! — cannot write!”

I was recently reminded of this poem when a long-time friend came by my office with some books in different Kenyan languages: Yahya Mutuku’s Tunanie Kikamba: Ivuku ya Amanyiwa, Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s Kenda Muiyuru: Rugano rwa Gikuyu na Mumbi, and collectively authored Nafufurahie Kigiryama targeting different levels of learners’ competence.

Except for Ngugi’s, the other books were primarily designated for the current “Competency-Based Curriculum” for schools.

As we got talking about the dynamics of publishing in mother tongue in Kenya, we revisited the then public debate on the schools’ curriculum review process, and the historical language debate in African literature, about which I shall comment shortly.

The merits or demerits of the revised curriculum aside, my interest in the texts that my friend had was literary; precisely, the place of language in the dynamics of literary and cultural creativity, circulation and consumption in the era of cultural and linguistic paradoxes — for instance, the general dearth of traditional reading cultures in favour of digital access to information, to say nothing about a growing population of Kenyans who can neither read nor speak their mother tongues.

At a time when communicative incompetence in both spoken and written mother tongues has become the norm, how can Kenyan writers imbue cultural originality in the literary works that they hope to create?

From historical and ideological perspectives, both the curriculum review and the publications in Kenyan languages are certainly the most recent push in a long and hard-fought intellectual project of restoring the African’s voice in the global terrains of knowledge.

As colonialism tottered to its inevitable end in Africa, debates on the language of, and in, literature began to preoccupy African creative and critical intellectuals. Creative trailblazers including Shaaban Robert, Mazisi Kunene, and Daniel Fagunwa recognised the symbolic and functional importance of writing in their mother tongues and later, critics such as Obi Wali and then Ngugi wa Thiong’o pushed this option as a subject of discussion by the literary professoriate in conference halls and peer reviewed journals.

Subsequently, African literature is currently richer with novels such as Robert’s Kusadikika and Fagunwa’s Ògbójú Ode ninu Igbo Irunmale (The Forest of a Thousand Daemons), not only for their deep understanding of societal issues and sophisticated stylistic expressions, but largely because of the idiomatic value of the languages of their creation.

Both Kiswahili and Yoruba, which I use for illustrative purpose only, have subsequently acquired more secondary speakers and greater significance in Africa’s geopolitics; Kiswahili, for instance, which was recently introduced in the South African school curriculum, is also one of the languages adopted for official use by the African Union. Is it possible that the good fortune of Kiswahili and Yoruba, in their continental recognition and spread, was because of the pioneering writings of Shaaban Robert and Daniel Fagunwa.

Further, the growth of African literature in Kiswahili and Yoruba has offered a life insurance of sorts to these languages that are now relatively secure from the risks of language death, which is the grim reality that ominously haunts many African languages. At this rate, what other African language in Kenya has future prospects of spread and recognition as Kiswahili?

LINGUISTIC DEATH

As we slowly render African languages in Kenya redundant in literary creation and daily socialisation, we condemn these languages to linguistic death, which is the point that Simon Gikandi makes in The Fragility of Languages.

Citing many critical sources, including the eminent linguist David Crystal, Gikandi bemoans the tragedy of “a language dying out somewhere in the world every two weeks or so.”

Any threat to a language is also a threat to literature and, if you ask me, a literary work created by someone with a flippant grasp of their mother tongue generally lacks an aura of authenticity. Although I can get local examples, let me reach out to Nigeria, where Chimamanda Adichie’s works are globally celebrated partly because her craft is peppered with her knowledge of the Igbo language, its idioms and its primary geographies.

If we let our languages die, by disuse in our creative industries generally and literatures specifically, we are headed for a literary cul-de-sac envisioned by Obi Wali in The Dead End of African Literature.

Because of this, I fear that currently, Kenya’s literature is in the sick bay — and the prognosis is shifty — because upcoming writers are deprived of the analytical depth and nuance that could be easily acquired through mastery of their mother tongues.

You can imagine my joy, then, when my publisher friend assured me that East African Educational Publishers, the most enduring and perhaps most successful publishing firm in East and Central Africa, has commissioned writers to create literature in Kenyan languages, targeting young readers.

Only such initiatives will, ultimately, save us from the risk of creative irrelevance. Because at the core of global conversations, is the presumption that people bring their experiences to the table, in their own languages, before they can stake any claims of having contributed to the best of world literary heritage.

Here in Kenya, this view was fronted exactly 50 years ago, by Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Taban Lo Liyong, and Owuor Anyumba who authored their much cited manifesto, “On the Abolition of English Department.” They argued for the centralisation of “Kenya, East Africa, and then Africa in the centre” in the literature curriculum which had previously been animated by the values of Englishness.

For Ngugi, Taban, and Anyumba, political independence had not extended to ideological or curricula independence, and so the manifesto launched the process of what Ngugi, almost 20 years later, would term “decolonising the mind”, a process that remains current 50 years later, with echoes across Africa.

Yet, if Ngugi’s idea of decolonising the mind was supposed to be a conceptual reorientation of our ways of seeing our worlds, and of bringing our experiences under our discursive control, the same remains an incomplete but necessary project, partly because the idea only found relevance in sections of the academia, while completely lost on the government bureaucrats who remained stuck in the grove of Englishness.

And so although the Ngugi team eventually succeeded in reconfiguring the literature curriculum at the University of Nairobi, other institutional traditions and structural processes of education, public service, and socialisation remained overshadowed by neocolonial strictures.

Notably, however, there is a resurgent interest in decolonising the mind, a process whose grammar has now attained broader relevance, and is now used in contexts far wider than literary and cultural studies.

Wherever structural power inequalities perpetuate social injustices that contradict the growing embrace of the ideals of democracy, human dignity, and concern for minority rights, calls to restoration of any balance whatsoever have been couched in the vocabulary of decolonisation.

We now know that decolonising the mind cannot succeed if we limit the initiatives to university level literature departments alone, but by embracing a broad-based curricula approach that targets young and old scholars in other sectors beyond education.

That is why, as the Ngugis, Yahya Mutukus, John Habwes and others write in indigenous Kenyan languages, the State should support such initiatives through proper policies such as structured subsidies to publishers; and possibly requiring students to demonstrate working knowledge of at least one Kenyan language other than their mother tongue.

Only then can we begin to heal Kenyan literature, pull it from its sick bed, and push it to confer with its contemporaries in South Africa, Nigeria, and even Uganda, who have recently made light work of us in regional and global awards prizes.

Dr Siundu teaches at the University of Nairobi.