Inspiring tale of disability and the long road to acceptance

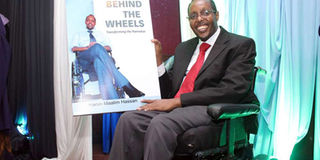

Mr Harun Maalim Hassan (right) during the launch of his book, Behind the Wheels, at KICC in Nairobi on March 23. DENNIS ONSONGO | NATION

What you need to know:

- Using a personal lens to mirror and give a reflection on his life, the last born in a family of 30 children says that disability is an expensive proposition.

- He opines that demanding physiotherapy, physical props such as prostheses, wheelchairs, polio braces, and non-prescription medication leave many PWDs at a disadvantage and more often in great suffering.

Harun Maalim Hassan’s Behind the Wheels is an autobiography that succinctly captures the plight of persons with disabilities in a manner that places the reader in an emotional rollercoaster.

The 202-page book follows the life of Hassan, a paraplegic, as he struggles to make a lemonade out of a plethora of lemons presented to him by a sudden turn of fate that leaves the once budding Bachelor of Arts Degree in Environmental Studies graduate paralysed from the waist down.

The winner of the Malaika Tribute Award and a public administrator-turned disability rights advocate, recollects his life, rising from an academically slow boy from Dandu, Takaba sub-county in Mandera County to a District Officer before a date with destiny in March 2017.

At the age of 28, his life takes an unexpected twist after a car crash changes his life forever. He, however, overcomes all the troubles and continues with his life like nothing happened.

The man from Kutulo in Mandera County takes a voyage into the world of disability with a surgeon’s precision battling common fallacies associated with disability and societal distortion and perceptions and emerging issues in the management of disability.

He seeks to deconstruct the common distortions that people with disability have impaired professional competencies, have lost the ability to function as productive members of society, are helpless and in need of hand outs and that children with disabilities are a blemish on the family and society.

He uses the example of himself and other persons with disabilities to illustrate his point that the societal perception of disability being synonymous with inability does not hold water. He learns to drive himself, holds a public position, is married and also presents his other physically challenged friends who are in formal employment and are leading a normal life just like those without any form of disability.

“Whatever disability may be, the true symbol of disability has become the wheelchair. It matters little that disability can be mental, physical — indeed even moral,” he says.

However, he is at pains trying to narrate the challenges persons with disabilities go through in life. And who better to narrate the story than Hassan, who is now a paraplegic after suffering a horrific spinal injury that leaves him paralysed from the waist down.

Using a personal lens to mirror and give a reflection on his life, the last born in a family of 30 children says that disability is an expensive proposition. He opines that demanding physiotherapy, physical props such as prostheses, wheelchairs, polio braces, and non-prescription medication leave many PWDs at a disadvantage and more often in great suffering.

He says that every single day is a battle for a physically challenged person: from societal stigma emanating from belief that the situation is a curse, discrimination, trauma, marginalisation and the battle to overcome denial in the transition phase of trying to accept a new condition.

The book is divided into two parts — Book I and Book II. Book I introduces the life of the writer from his birth through his dreams to the end of the dream, which comes abruptly to a halt following a car crash in March 2007 that turns the budding author into a paraplegic.

The second part looks into his life after paralysis, understanding the life of disability and giving back to society through advocacy.

The book opens with a young Hassan who is serving as a District Officer dreaming big. The Kenyatta University Bachelor of Arts in Environmental Studies graduate dreams of making forays into the murky but captivating waters of Kenyan politics as a Member of Parliament for Mandera West constituency after drawing inspiration from the swearing in of President Mwai Kibaki.

His political dreams are, however, cut short through a phenomenon currently known as negotiated democracy, a collective decree made by a council of elders that must be respected, when he fails to win the approval of his Darawa sub-clan at the clan primaries in a crowded field of eight aspirants.

But the loss would not deter a determined Hassan who wanted to represent his people of Mandera West. His thirst for greatness leads him to Takaba town where he also fails to get the nod from the Takaba clan to vie for the coveted seat.

He resigns himself to being a District Officer, and it is on his journey back to Nairobi from Mandera to be posted as a District Officer that the cruel work of fate changes his life after a car crash. The event at Chabi Baar rewrites the script of Hassan’s life. Hassan’s dream is shattered.

The reader gets introduced to the life of persons living with disability. The transition from his old way of life to the new one becomes conflicted, he is stuck in denial — a first phase that newly disabled individuals go through. He wishes to die so that he can save himself from the current misery he is going through but a strong family support lifts him from despair to the stage to partial acceptance.

Camel meat, traditional herbs and Quran recitations and prayers are prescribed with the belief that the paralysis would be reversed in due time. All these fail. Hassan finally embraces his state after a visit from his father. He starts taking initiatives like asking for food, taking a bath and he resolves to return to Nairobi to resume his work, abandoning his secret dying wish.

Hassan’s life takes a positive transformation and he starts to philosophise on issues of disability, like efforts to address disability, mainstreaming it into the social life and how society views persons with disability.

In part two of the book, the author focuses on advocacy work. With the political fire still propelling most of his actions, Hassan embarks on tackling disability as a philosophical and political ideology by forming an advocacy outfit, the Northern Nomadic Disabled Organization (NONDO) to advance his ideas.

“I want to change this narrative and make the public aware that behind the disability is a human being who is seeking to control his own life and story,” says Hassan.