Village memories that I still carry

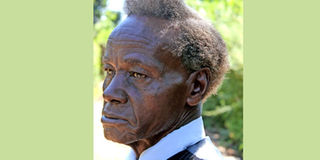

Mr Rucibi, with his characteristic hairstyle, could not be bothered to smile for the camera. PHOTO| BILL RUTHI

What you need to know:

- We carry history; it’s the one thing humans cannot buy back, or towel off.

- In the past one and a half years, I have been possessed with history — mine and ours.

- We are bottled at source and those who care after our welfare, and also our accidents — all of them hope the seal will not be found broken.

To borrow from the title of Binyavanga Wainaina’s book, One day I’ll write about this Place, I suppose one day I will write about this place; in full length and colour. It will be at a later date, though.

Right now I am content with the notes — spirals of them, and content — to use the millennial-age era phrase, ‘Trusting the Process’. The world is full of colour, and if you are lucky enough, you discover you are part of the rainbow.

As December of 2017 segued to January, the jacaranda had shed their purple plumage and with each passing day, the land appeared bare, the trees scrawny. The rivers gave up their water at the behest of the scorching January sun, revealing charcoal-black rocks that resembled sunning baby turtles.

Now when I took my camera for the obligatory visit down to the river, I stepped barefoot into the water. The rivers were roads. It was during such a walk that I met a man who went by the name Charlie. A wiry man who wore a Donald Trump-like red cap, hair flying out the sides, Charlie stood by a tree hard by the banks, waiting for the fish to take the bait.

We got talking in between scoops of snuff up his chimneys. He made a living selling fish and making sandals fashioned from old car tyres, he said. The sandals could last a lifetime and a bit in the afterlife, Charlie, a storyteller, announced.

He owned a piece of wooded land across the river, living in quiet hermitage. An effortless storyteller, he regaled me with tales. The conversation spun to his life, more to the point, his status. There was a lady — a Somali who lived in Nyeri town — Charlie said; a fetching woman who “wondered why the heck I haven’t sent word for her.” It was Sunday afternoon and the fish stayed in school.

Gone country

It will never be the same again, which of course is the way of life. If there ever was an indication of the inevitability of change, then the cattle dip is it.

Those structures — bath tubs, really, albeit with more traffic, where cattle waded into for a bath at least once a week — are now relics. Farmers, concerned that their animals emerged from the brackish water dirtier and mangier than when they dived in, chose to hose down their cattle in their sheds at home.

To the untutored, the cattle dip would be just that, a cattle dip. But when they operated, when chairpersonship was an elective post, they resembled something close to a catwalk, with cattle walking down the gangplank. But the structures live on, these crumbling museums, these front-seats.

Men of consequence

When I first met him, he was on his way to church. He was a proper man, outfitted in a coat vest, and for a moment it was as if we had time-travelled to 1969. The man, who would later become a friend was a museum all his own.

Mr Rucibi’s shock of greying hair was parted to the side, and the front defied gravity. Even Don King, the boxing promoter, couldn’t touch him.

“It has been like this for years,” he told me. In the old days, when his style was in vogue, one didn’t need a comb to part the hair; in the hirsute of happiness one only needed a porcupine quill, run it through the hair in a straight line and you were in circulation.

Mr Rucibi had been in circulation, still was. He cut a stern, head-masterly outlook. He was a complete stranger but you only encounter such a man once, and so I asked if I could take his picture. He snuffed out the burning end of his rolled tobacco. But my attempt to have Mr Rucibi smile for his portrait came back empty.

“Just let me have a printed copy,” he said curtly, then lit up his tobacco roll and walked up the road to join fellow parishioners.

It is 3:51am as I write this. I can hear roosters turning on their ancient clocks. It is one of those sounds that have remained impervious to time and seasons.

But some threat looms up ahead; with more and more people abandoning free-range birds for the genetically engineered ones, how long will the music last?

Not too long ago, I dug out a shovelful of undeveloped film exposures — negatives, as most people referred to them before the cell-phone killed photography. They must have been from the 1970s. Holding them against the light, I recognised only a few people; the rest were ghosts, silhouettes, people trapped and held against their will. They will remain that way.

When I took the rolls to photo studios in Nyeri town, and later to Nairobi in a bid to buy freedom for the strange people, I was met with the same answer: We don’t do these anymore. Change, that’s what. There was a sinking feeling, a strange voiceless sound; like the sound of a soul being carried away from this earth.

A keepsake for all time

My great-grandmother died in 1986, at 102 years. When they buried her, they made sure to include her loyal walking sticks and also her old wooden box. I have never understood why the decision to bury her with the canes was made. Surely she wouldn’t need them to ford across the proverbial river.

But the family kept her kitchen stool — a four-legged seat hewed from a log. It had been a present from her husband — though no such term could have been used. But it qualified for a present.

After the matriarch — a diminutive woman who had served as a mid-wife, a broker of life — died, her stool moved into my grandmother’s kitchen.

Learning of its history, I dragooned my grandmother to transfer ownership. At first she resisted, but I wore her down and carried it home. It sits in a corner in the study. It is the closest to an heirloom. In the stool’s contours and grooved seat lives history. There is presence there; of the man who carved it, and the woman who kept it, and who outlived her husband by 39 years.

We carry history; it’s the one thing humans cannot buy back, or towel off. We are everyone, and one only has to dig around.

In the past one and a half years, I have been possessed with history — mine and ours. There’s healing in there, too. We are bottled at source and those who care after our welfare, and also our accidents — all of them hope the seal will not be found broken.

The promise of a welcome

I travelled down the dirt road one last time to the river and walked over the log bridge that had once appeared so frightening. To the left of that rickety bridge lay what I once was; to the right were cobblestone sidewalks and the waiting new. This was goodbye; and the promise of a welcome.

About two weeks ago, two events of historical import took place, and both had to do with the Nation. Last month, the Nation ran a story about a CDF-sponsored community hall. The building, it turned out, is built on a mass grave of captured Mau Mau freedom fighters.

Concerned citizens, some of whom had seen action during the struggle for independence, had for long fought for the renaming of the hall in honour of the slain. This past week, the hall was officially gazetted as a museum and renamed Mau Mau Memorial Hall.

Recently, a pair of Belgian documentary makers sought the Nation for a story the paper ran late last year. The story was about two trees in my village, Kagumo in Nyeri, that have stood for over 100 years, and atop which the British had installed a watchtower to monitor the movements of Mau Mau freedom fighters during the State of Emergency.

Piqued, the men got in touch. Two elderly men, one of whom had featured in the story, titled Trees with dark history still stand, were on the set, and they rehearsed the history of the trees and of that period.

As the interview wound down, the two men elected to sing the British anthem that they had sang as children. You could search forever and not find music more disjointed than the rendition. But they sang, and in the song and the men’s memory, you couldn’t find a more memorable pair.

These are things I’ll carry.