Philately: An art lost in the vortex of modern technology

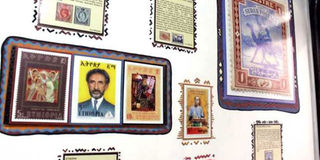

A section of the Murumbi stamp collection at the Murumbi Gallery in Nairobi. PHOTO | FILE | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- The peerless material includes paintings, photographs, sculptures, masks and other trinkets.

- The postage stamp and the taste of the adhesive on the back is now all but forgotten.

The Joseph Murumbi collection – an assemblage of rare items of art from all over Africa – is perhaps the most unique and comprehensive of its kind by an individual, at least on the African continent.

The collection, housed at the Kenya National Archives and also at the Murumbi Gallery – the tiny building near the junction of Kenyatta Avenue and Uhuru Highway in Nairobi– was sold to the government of Kenya by Murumbi, Kenya’s second vice-president and the shortest tenured second-in-charge (he resigned after six months in office in 1966).

The peerless material includes paintings, photographs, sculptures, masks and other trinkets. But as much as any, it is Murumbi’s impressive stamp collection that stands out, especially in light of the dwindling interest in philately, a hobby lost on an entire generation in the wake of the wildfire of technology in the past one-and-a-half decades.

AVID TRAVELLERS

The replicas of Murumbi’s stamps, which he amassed with his wife Sheila – both avid travellers – date back to colonial Africa; the sun-filled days of newly found independence; stamps bearing faces of distant rulers, sporting heroes and commemorations of important dates.

The postage stamp and the taste of the adhesive on the back is now all but forgotten. Trends indicate that fewer and fewer people make the trip to the post office to mail or receive a letter, unless for utility bills or courier and bulk mail, or perhaps while sending an exam success card. The email, text messaging and mobile phone voice calls obviated all that chase.

A recent spot-poll by this writer in the streets of Nairobi revealed that only two out of 15 people polled had bought a postage stamp or sent a letter via ordinary mail in the past one year.

As a young woman in the 1970s and 1980s, Juliet Barnes looked forward to the trip to the post office in Nyeri. Each time she collected the family letters, she would tear the stamp off the envelope and slip it into a folder. Over the years, her stamp collection grew: The thumb-nails were little markers of memory and stages and also family. Later, when she began raising her own family, her son inherited the collection and began adding his own.

COLLECTION

The collection now reposes somewhere in her house; she’s not certain where. “They are there somewhere,” says Juliet, a historian and author of the book, Ghosts of Happy Valley. “I no longer collect, but it was a lot of fun; the pictures of flowers, animals, the people. The stamps were from all over the world.” Like Juliet, Bernard Mwangi grew up fascinated with postage stamps.

His collection is newer, but the majority of the stamps are post-marked to the tail end of the 1990s, with a few from early this century.

His interest dwindled after it became obvious that ‘snail-mail’ was capitulating to the blinding speed of e-mail.

Mwangi, who works in Murang’a town, is sentimental about his pieces. “I treasure the collection,” he says. “So many things have changed, so it is good to retain what was once a very important part of the process of communication.”