Of literature, empty life choices and a life turning out empty

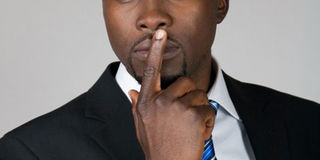

Sometimes a promising career, business, healthy body or a relationship all blows up and suddenly turns out empty. PHOTO| FILE| NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- It’s hard to describe the pain of loss in a child’s face who had picked an “empty” fist.

- It was utter disappointment. In life, however, things are not as easy in knowing which the “empty” fist is.

- Sometimes a promising career, business, healthy body or a relationship all blows up and suddenly turns out empty.

One recent evening, I went for a jog with my children in the neighbourhood. Then there was a memory of desperate yearning.

Something in the air smelt like an afternoon from my childhood in the hills of Taita – cut grass, smoke and the whiff of dry season air.

Whenever that happens, I see the lush village paths, the blinding noonday sun, I hear the loud voices of the women dexterously balancing loads on their heads and I even see fireflies, the darting of the first bat in the evening light and hear the clop-clop of cows’ hooves as a late shepherd rushes them home.

It was all welcome noise from the past; what one writer called “dissonance made eloquent”. Then I remembered a game we played when we were little children.

We would close our fists but one of the fists, either the right or left one, would have a sweet or something else in it. It was one’s duty to choose which fist had something. We tried hard to avoid choosing the “empty” fist.

It’s hard to describe the pain of loss in a child’s face who had picked an “empty” fist. It was utter disappointment. In life, however, things are not as easy in knowing which the “empty” fist is.

Sometimes a promising career, business, healthy body or a relationship all blows up and suddenly turns out empty.

In his novel, Waiting for the Barbarians, J.M. Coetzee paints the picture of a man who wonders if he has picked the right fist. It’s the portrait of an aging magistrate who lives among the colonised (called barbarians) and he has the unenviable duty of representing the Empire (coloniser). He has led a peaceful and comfortable life and wants to continue as before. However, change knocks down the gates. He learns that the Empire is planning to kill some of the barbarians to probably teach all the others a lesson in humility. The New York Times’ Roger Cohen described the book aptly as “the portrait of an ageing man, stung by his conscience, bewildered by his times”. Oh that bewildered part!

As a corporate leader, the novel struck a note. Like in the novel, change is everywhere in corporate circles from changing business models to dealing with different cultures at work. Industries are merging and some businesses are disappearing overnight as others appear at lightning speed.

Presidents, politicians, chief executive officers and managers are all bewildered by their times. Countries are on tenterhooks; economies tumbling and jobs evaporating. Politics is changing and becoming ever more unpredictable, either swinging to the far right or left.

In the novel, the Empire was faced with new challenges and a rebellion that threatened its very existence. A narrator says: “One thought alone preoccupies the submerged mind of Empire: how not to end, how not to die, how to prolong its era. By day it pursues its enemies. It is cunning and ruthless, it sends its bloodhounds everywhere. By night it feeds on images of disaster: the sack of cities, the rape of populations, pyramids of bones, acres of desolation.”

The leaders of the Empire felt besieged by forces they could not control and they resorted to quelling rebellion among the colonised barbarians by using brute force.

“The jackal rips out the hare's bowels, but the world rolls on.” The empire is dying and the magistrate is also dying. Cohen sums it up by saying that “this is a desperation of mortality”. This desperation of mortality has gripped nations, corporations (with dwindling profits) and non-governmental organisations (with dwindling financial support).

The Empire sends an army to hunt down the barbarians but they are too elusive. The Empire’s soldiers are lured deeper and deeper into the desert and mountains by the barbarians who then terrorise them. The ageing magistrate who represents a bewildered leader, echoes familiar words, “All that I want now is to live out my life in ease in a familiar world, to die in my own bed and be followed to the grave by old friends.” Sorry, sir, there is no longer a familiar world. Change rocked the boat.

FLEEING SOLDIERS

The magistrate decides not to leave his station among the barbarians even as the surviving Empire’s soldiers flee. They hunker down as winter looms waiting for the barbarians to attack.

“The first snow begins to fall. The magistrate reflects on the possibility that he lost his way a long time ago”. Maybe he picked the “empty” fist, after all. There may be heartbrokenness or maybe the tears. But he is not sure if he picked the empty.

Sometimes it’s easy to know when one picks the empty fist. At other times, it’s not. We sometimes make choices that bewilder us as it’s not easy to judge if we succeeded or not. Sometimes we feel like we succeeded. Almost. But not quite. Or in between.

The English critic James Wood, borrowing from the great Sigmund Freud on this, writes about “the slow revelation that I made a large choice a long time ago that did not resemble a large choice at the time; that it has taken years for me to see this; and that this process of retrospective comprehension in fact constitutes a life – is indeed how life is lived. Freud has a wonderful word…‘afterwardness’: it is too late to do anything about it now, and too late to know what should have been done. And that may be all right”.