Moi, the passing cloud that did not go away

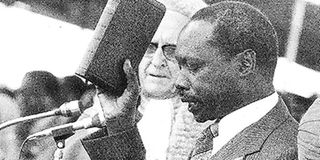

Mr Daniel arap Moi taking the oath of office as Kenya’s second president following the death of Mzee Jomo Kenyatta on August 22, 1978. The swearing-in ceremony was presided over by Chief Justice, Sir James Wicks. PHOTO | FILE

What you need to know:

- To succeed Kenyatta, Moi endured humiliation, some of it physical, from opponents that included powerful men who had access to Kenyatta. But Moi used, among other things, his open and unquestionable loyalty to Kenyatta as a stepping stone to power.

- Having changed the Constitution to get rid of political pluralism, Moi moved to construct Kanu into an enormous monolith with massive powers shared in equal measure by leaders at the national level and the grassroots.

- Angry demonstrations rocked the country as Kenyans decried what they saw as a return of political assassinations. Eager to keep his name clean, Moi invited the British Scotland Yard to investigate Ouko’s death.

Against the greatest of odds, Daniel Toroitich arap Moi, a shy and reserved former primary school teacher, took the oath of office to become Kenya’s President.

With the decisive hand of Charles Njonjo, the spirit and letter of the Constitution was enforced on the same day Mzee Kenyatta died.

“Daniel Arap Moi is now the president of Kenya for 90 days until an election is held,” Charles Njonjo told foreign correspondents.

“The Constitution says the VP will be sworn in and will be president for 90 days,” says Njonjo in an NTV documentary.

The 90 days elapsed, and Moi was confirmed president after being elected unopposed in the 1979 election. But those who worked hard to stop him from succeeding President Kenyatta dismissed him as a stop-gap president; and they had a term for it – a passing cloud.

“The people of central Kenya said he was a passing cloud,” recalls retired politician John Keen.

They were wrong, according to Moi’s press secretary Lee Njiru.

“Passing cloud because you think your backyard is going to determine who is a passing cloud and who is not to be? He (Moi) stayed on for 24 years, four months and eight days,” he retorts in an NTV interview.

But according to Mark Too, who would be Moi’s, Bwana Dawa (Mr Fix It), “Moi believed in destiny. I can tell you today Moi did not have a timetable.”

Observers of his ways say Moi made a career out of being undermined and touring the country delivering messages from Kenyatta.

“Kenyatta would not hear any nonsense. He would tell Moi’s detractors that ‘I saw Moi on TV greeting people in my name. What have you done for me?’”

To succeed Kenyatta, Moi endured humiliation, some of it physical, from opponents that included powerful men who had access to Kenyatta. But Moi used, among other things, his open and unquestionable loyalty to Kenyatta as a stepping stone to power.

Aware that he was regarded rather lowly, Moi’s immediate instinct was to fight for his own survival.

“Moi was hands on, he hit the road running,” says Lee Njiru.

In a move calculated at appealing to the Kenyatta base, Moi coined a slogan, Nyayo , Kiswahili for footsteps; his pledge to follow the ways of Jomo Kenyatta.

But skeptics saw it differently. To Raila Odinga, “It was artificial nyayo. In terms of content, they were totally different.”

Of the promise to follow Kenyatta’s nyayo, GG Kariuki who would be a powerful Moi ally says: “That is a saying anybody would say but find his own way.”

Moi retained much of the Kenyatta inner circle and specifically the man who ensured he became President, Charles Njonjo. In the circle, too,was GG Kariuki and the Vice President Moi had chosen, the urbane Nyeri politician Mwai Kibaki. Together, they constituted a form of collegiate presidency that saw them ride together in the presidential limousine.

Dr Richard Leakey recalls that Moi, Njonjo and Geoffrey Kareithi, the head of civil service, would have lunch together in one or two city restaurants almost every day of the week.

“We were with him for only three years. We were running the government that time,” recalls GG.

An event that happened exactly four years into Moi’s presidency changed the man forever. A group of disgruntled Air Force servicemen briefly overthrew the government on the 1st of August 1982, before being overpowered by loyalist forces commanded by Brigadier Mahmoud Mohommed.

“The problem was, of course, the 1982 coup,” says Muthaura. To Njiru it was the proverbial once beaten, twice shy.

From then on, an insecure Moi turned to the Machiavellian script, stripping the ranks, getting rid of Charles Njonjo and constructing his own power circle made of figures from his own Kalenjin tribe such as power man Nicholas Biwott and presidential fixer Mark Too.

“He (Moi) went somewhere in Kisii and said some foreigners were supporting somebody to take over the government of Kenya,” recalls GG of the beginning of Njonjo’s downfall.

Dr Leakey is more lucid. “It is said that somebody will put you there and become your worst nemesis because he knows too much about you to be safe. I think Moi felt the need, on advice from Biwott and others, to bring Charles down to a level they could handle him”.

That is how Njonjo would be removed from government.

Regarding Biwott, Cyrus Jirongo who was in Moi’s good books in the early 1990s says: “Some of us used to know exactly what used to happen. You wouldn’t believe it was Moi when you found him and Biwott arguing. and Biwott didn’t have the small voice he normally uses. You would think it was a lion roaring, and you would find Moi sometimes seriously subdued.”

A powerful provincial administration also meant an intimidating political environment. State agencies, which included the dreaded Special Branch, became part of Moi’s political arsenal deployed with single-minded brutality against political enemies, real or perceived.

“You were either loyal or a dissident and even loyalty had its degrees,” says Jirongo

Having changed the Constitution to get rid of political pluralism, Moi moved to construct Kanu into an enormous monolith with massive powers shared in equal measure by leaders at the national level and the grassroots.

Kanu branch chairmen in the districts were consequential to many political careers as was the dreaded Disciplinary Committee headed by South Nyanza political heavyweight David Okiki Amayo.

“I faced that committee,” recalls GG.

A master of parallel systems, Moi introduced regional pointmen as a separate tier of the complex power hierarchy he built.Essentially these point men were his friends, people he trusted; people who could take the proverbial bullet for him. People like Mulu Mutisya.

“He had his people everywhere. When in Nairobi, he knew he had Shariff Nassir in Mombasa, Angaine in Meru, Ole Ntutu in Maasailand, Omamo in Luoland and Okiki Amayo in South Nyanza,” recounts Lee Njiru.

“He knew everything that was going on. Moi had the ears of an elephant,” he says.

The president was also an accomplished master of the carrot and stick philosophy. He was reputedly generous with cash and other favours.

“He was a very kind man personally,” says Dr Richard Leakey a one-time head of the Civil Service who recalls Moi removing a pen from his pocket and money flying all over on the carpet.

But then others would debate where the line was drawn between personal generosity and what some called a bad culture of handouts that bred corruption. Stories were told of the dishing out of briefcases of cash at State House.

According to Nyachae, the money didn’t come from Moi’s business earnings because “the companies would have collapsed.”

But, interestingly, according to Nyachae, Moi never called him to release public money to him, but it was there in plenty.

“I went to State House, saw a room ringed with briefcases,” says Koigi Wamwere, adding that Moi never gave out money out of generosity. “He knew everybody had a price and could be bought.”

“There were briefcases. Big boxes used to come in every day” adds Dr Leakey.

The signature of Moi’s years of absolute power came in 1988, his tenth year in office. Political dissent had been completely subdued, and Moi’s word was law. In a dramatic departure from convention, Moi got rid of the secret ballot election and in its place, he introduced mlolongo, Kiswahili for queue.

Under this system, voters simply lined up behind the candidate of their choice. Polling officers drawn from the provincial administration then counted the voters but only declared as winners the candidates preferred by the Moi power centre.

The 1990s began on a sour note for President Moi and Kanu. In March 1990, Foreign Affairs Minister Dr Robert Ouko disappeared from his home in Koru near Kisumu. His charred remains were found a few days later in Got Alila, a hillside not too far from his home. Angry demonstrations rocked the country as Kenyans decried what they saw as a return of political assassinations. Eager to keep his name clean, Moi invited the British Scotland Yard to investigate Ouko’s death.

Moi’s confidants Energy Minister Nicholas Biwott and Office of the President PS Hezekiah Oyugi were briefly held over Ouko’s death and released. A judicial commission of inquiry headed by Justice Evan Gicheru was dismissed before it completed its work. To date, the killer of Robert Ouko has not been publicly identified.

In the same year, another suspicious death was to rock Moi’s regime. Defying a death threat by cabinet minister Peter Okondo, the fiercely vocal Anglican Bishop Alexander Muge travelled to Busia and just as warned by Okondo, did not leave alive. Muge was killed in a road accident in Turbo, but many believe it was an assassination.