Kenyan teaches world how to join solids without using heat

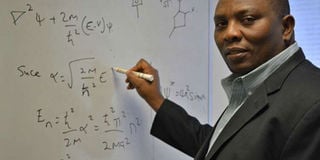

Martin Thuo, a professor at Iowa State University in the United States. PHOTO | COURTESY

What you need to know:

- Martin Thuo was so irritated by noise coming from welding works near a house when he visited Kenya in 2011 that he started wondering whether he could create a system that allows metals to be joined in silence.

It was not until 2014 that he finally figured out how that could work.

The light-bulb moment came when he drew inspiration from a project he was engaged in, which involved liquid metals.

In that joining process, there is total silence at an environment-friendly setting.

They realised that if a molten metal was enclosed into shells then the shells are ruptured at the right place, it could lead to the joining of two surfaces.

Scientists worldwide now know it is possible to join two solids without welding or using heat, thanks to an invention by a team led by a Kenyan professor working in the United States.

Prof Martin Thuo, currently a professor of engineering at Iowa State University, was so irritated by noise coming from welding works near a house when he visited Kenya in 2011 that he started wondering whether he could create a system that allows metals to be joined in silence.

“Someone was working on welding a gate and the noise coming from their work was just excruciating, especially after 20 hours of travelling and a late night catching up with the family,” the chemistry expert told the Nation.

It was not until 2014 that he finally figured out how that could work. The light-bulb moment came when he drew inspiration from a project he was engaged in, which involved liquid metals.

Working with a research team he founded in 2014 that now has 11 members, he figured out a complex process in which two different surfaces can be fused using cooled metal rather than heated one.

In that joining process, there is total silence at an environment-friendly setting.

They realised that if a molten metal was enclosed into shells then the shells are ruptured at the right place, it could lead to the joining of two surfaces.

'TO SOLIDIFY'

“The particles we made can be envisioned as balloons containing a liquid which when punctured release the liquid. But in our case, this also allows it to solidify,” explained Prof Thuo, who obtained his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in chemistry from Kenyatta University between 1996 and 2002.

“The question then was how we could keep the metal from becoming a solid once inside our shells. The solution was hidden in the shell itself since we could engineer it to keep the molten metal liquid even after cooling it below its melting point,” he added.

The professor has created a company, Safi Tech, which he says is moving the invention to commercialisation.

Details of the welding process were published in the Scientific Reports journal on February 16, 2016, where Prof Thuo and his team explained the areas where their innovation can be used.

Among them, they wrote, is “healing of damaged surfaces and soldering/ joining of metals at room temperatures without requiring high tech instrumentation, complex material preparation, or a high temperature process”.

“Manufacturing by means of undercooled particles could also be used for healing damaged surfaces such as cracks, scratches, or other defects below the microscale as long as the surface bearing the defect can bond (chemical or mechanical) with the undercooled metal upon solidification,” they stated.

EARNED ACCOLADES

Publication of the work earned him accolades from a number of pro-innovation think-tanks in the US.

The Chemical and Engineering magazine, published weekly by the American Chemical Society, listed it among the notable chemistry research advances of 2016.

“Martin Thuo’s group at Iowa State University exploited the spontaneously forming oxide skin of bismuth-indium-tin and related alloys to keep microscopic liquid metal droplets from solidifying, even at temperatures below their melting points.

“The researchers showed that applying a gentle force to the droplets breaks the shells, causing the metal to briefly flow before the skin re-forms. They used that property to bond metal parts together at room temperature, in effect soldering without electricity or heat,” the magazine said.

IDTechEx Printed Electronics USA also listed the invention as the best in one of its three categories under which it honours new ideas every year. Safi Tech was given the Best Technical Development Materials Award.

“The judges commented on the need for the solution offered by Safi Tech, where a room temperature, cure on-demand solution would be very valuable,” says a November 17, 2016 article on the IDTechEx website.

Prof Thuo said the accolades had warmed his heart.

'VERY INSPIRING'

“Getting these recognitions is validating and inspiring. It is very inspiring to the post-docs and students who run the experiments as this is truly a team effort. It also helps us share the work with a wider audience, which is key to getting quick adoption,” he said.

The professor said the innovation will change the world in many ways.

“A key challenge in joining, especially in the electronic devices is the emergence of plastic substrates that cannot tolerate temperatures above that of boiling water. Our technology will allow companies to solder components on these substrates without high temperatures and we hope that this will accelerate innovation in electronic devices,” he said.

He added: “We also hope that challenges in power supply can be overcome and workplace hazards minimised for those working in joining metals. Above all, this technology opens up the area of so-called meta-stable materials as affordable and green solutions to some common day-to-day challenges.”

Prof Thuo reckons that there are not many Kenyan scholars in the US but is proud of some of the work done by Kenyans.

“Kenyan academics in the US are few and with an increase in the number who are coming back to Kenya after their PhDs, I’m not sure where this number will be in future. There are notable discoveries from Kenyans in the diaspora. Most significant are the cures discovered by Dr George Njoroge of Eli Lily and his team,” he said.