2007 violence led to the birth of new laws, but wounds still hurt

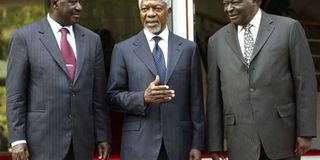

From left: Opposition leader Raila Odinga, former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan President Mwai Kibaki during negotiations to end the 2007 political stalemate. FILE PHOTO | REUTERS | NOOR KHAMIS

What you need to know:

At the global front, the government has lost steam in its quest to withdraw Kenya from the Rome Statute.

- Reflecting on the events a decade later, leading politicians give varied opinions on the strides the country has made.

- Mr Ruto argues that the peace currently witnessed in the Rift Valley is a product of their alliance with Mr Kenyatta.

Ten years ago today, the country was on the edge following the announcement of President Kibaki as the winner of a disputed election, triggering an unprecedented wave of violence that left more than 1,300 people dead and more than 650,000 people uprooted from their homes.

A decade later, the wounds have refused to heal with presence of the Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) across the country being a stark reminder of the terrible events that shook the country’s nationhood to the core.

While the Jubilee administration maintains that the country has healed, the termination of charges against the six suspects of the post-election violence (PEV) that included President Kenyatta and his Deputy William Ruto at the International Criminal Court in The Hague has meant that the debate is relegated to the periphery with politicians from across the divide vowing that never again should the country be subjected to such an abyss even though their actions and utterances in the last polls appeared to betray such a position.

NEW CONSTITUTION

The 2010 Constitution and other accompanying reforms were the products of a negotiated settlement led by the former United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan.

It is the new set of laws which ushered in devolution that has seen 47 distinctive units of governance established across the country. Independent commissions have also been created.

At the global front, the government has lost steam in its quest to withdraw Kenya from the Rome Statute which creates the ICC, a move that was meant to spite the court.

REFLECTIONS

Reflecting on the events a decade later, leading politicians, some who participated in the talks that saw Mr Kibaki and his nemesis Raila Odinga agree to share power, give varied opinions on the strides the country has made.

“Today, Kenya boasts independent and robust institutions like the Judiciary, which can easily rule on an issue without fear or favour, something that could not have happened under the previous constitution without severe and serious consequences,” maintains Mr Ruto who participated in the Serena talks that midwifed the deal that ended the 2007-2008 violence.

Mr Ruto argues that the peace currently witnessed in the Rift Valley, a region which bore the brunt of the violence, is a product of their alliance with Mr Kenyatta.

JUBILEE

“Jubilee was borne out of the spirit of this new covenant; as a political organisation committed to the reconciliation and unity of all communities in the republic starting with those whose unity was long written off as a political impossibility,” he explains.

The ICC cases became the hip bone that joined Mr Kenyatta and Mr Ruto into an alliance onto which they rode to power in 2013.

Even though Mr Kenyatta and Mr Ruto enjoy immense camaraderie today, talk that their divorce could occasion another round of violence in Rift Valley has refused to die in spite of the assurances from the duo that their alliance is here to stay.

REPEAT VIOLENCE

Amani National Congress (ANC) party leader Musalia Mudavadi, who led the ODM side in midwifing the peace accord, says the possibility of a repeat of the violence still lingers because of injustices committed by Jubilee.

“As the Kriegler Report and the CJRC report on historical injustices attest, Kenyans didn’t kill, maim and displace others for the fun of it. There were underlying unresolved issues of inequity that had been peppered over since independence. These germinated into ethnic profiling and hate. It is regrettable that 10 years on, the same issues are at the core of ethnic suspicion, animosity and the emergence of politics of exclusion via electoral injustice perpetrated by Mr Kenyatta’s regime which suffers serious legitimacy issues,” he says.

One of the phenomenal results of the PEV has been the conscious decision by Kenyans to settle in areas they feel safe in during politically volatile times.

NATIONAL COHESION

Many have had to sell their land and properties in different parts of the country to relocate to friendlier areas, a blight on efforts at national cohesion and integration.

Mr Mudavadi insists that the country has come full circle, clawing back the gains won through the enactment of the Constitution, backtracking on police and land reforms.

“Emasculation of independent institutions into irrelevant treadmills for Jubilee shenanigans, closed doors on accountability in the promotion of corruption, and dismembered fragile ethnic relations are the order of the day. It is like reading a local version of Blaine Harden’s Dispatches from a Fragile Continent all over again. To paraphrase Blaine, Jubilee duo is lurching between an unworkable pompous Western present and nostalgia for a collapsed dictatorial past.”

PEV VICTIMS

He regrets that justice was never accorded to victims of PEV.

“No one can account for the number of IDPs whose figure has kept mutating even as at now. There were resident IDPs who were displaced from their homes, their property usurped while others were transiting traders. This got disproportionate ‘compensation’. But how were those killed, of whom police shot 400, compensated? Of the former, there were the ‘integrated’ IDPs who received the worst treatment of being abandoned by government,” he explains. In June, for instance, IDPs held demonstrations demanding compensation with reports that some who are not genuine had infiltrated the lists to benefit, scuttling the process.

Their counterparts who had crossed over the border to Uganda returned home and police had to use force to disperse some of them after camping outside the National Assembly for days to get the attention of lawmakers.

They were never paid.

Mr Ruto and Mr Mudavadi were on the same side of the talks but today belong to opposing camps.

MEDIATING

Marking the ninth anniversary of the bloodletting earlier in the year, Dr Annan said that his role in mediating was amongst the most intensive and enduring of all of his interventions across the globe.

“Several key elections in Africa have unfolded much more peacefully since then, but we still have a long way to go,” he said.

Every African, Dr Annan said, must be able to trust in “our political institutions, in the supremacy of the rule of law and in the accountability of our leaders.” A member of the committee of experts (CoE) that drafted the Constitution, Mr Bobby Mkangi, says the blood, sweat and tears that flowed during the search for a new Constitution and the PEV were not in vain.

“They were a source of fresh inspiration in the quest for a new Constitution. Seven years have lapsed since this desire was realised. Ten years have also passed since the PEV,” he notes.

ELECTORAL JUSTICE

He, however, cautions that in as much as violence of the magnitude and trends witnessed in 2007/8 was not witnessed in the 2013 and 2017 presidential elections, it would be perilous and deeply flawed for anyone to entertain the theory that the promise for electoral justice as envisioned in the 2010 Constitution has been achieved.

Observers agree that there can never be peace without justice, be it on electoral matters or the general criminal justice system.

“Nobody in his right frame of mind should raise a finger against his neighbour when the winner in any electoral contest is allowed to have his win. It is that simple,” Mr Tom Mboya from Maseno University holds.

TALKING POINT

The shadow of PEV will always linger on the country’s history every electoral cycle.

In fact, it remains a talking point whenever politicians are campaigning.

On a positive note, even though the Presidency remains as lucrative as it is attractive, the devolved form of government has meant that considerable pressure has been removed from it as 47 regions tussle over who should be the governor, a powerful position that controls resources sent to counties by the exchequer.

And with the peril of winner-takes-all model of our national politics, which has made presidential ambition a matter of life and death for the top contenders, a proposal to adopt a parliamentary system of governance, or better still rotate the presidency, is fast gaining currency in what could shape the debate going forward.