When Moi reported elite land grabbers to the British

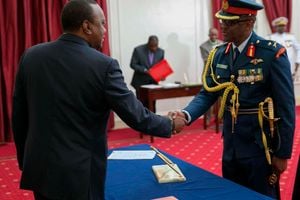

Daniel arap Moi is sworn in as the second President of the Republic of Kenya on October 13, 1978. He was implicated in land scandals. PHOTO | FILE | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- Moi’s complaint was that land bought for the settlement of squatters using British money was being sold to his colleagues in the government.

- The increasing reports of farms falling into the hands of well-connected individuals were becoming a concern to the British Ministry of Overseas Development.

As vice-president, Daniel arap Moi once reported to the British government about irregular acquisition of land by elites in the Jomo Kenyatta administration, confidential archived documents show.

It was a bold move at the time but would prove ironic in later years when he became president, since he was also implicated in many land scandals.

Moi’s complaint was that land bought for the settlement of squatters using British money was being sold to his colleagues in the government.

Before 1970, the money used for buying and distributing land initially owned by white settlers to displaced Africans was provided as loans by Britain.

The British also contributed to the expenses of the actual settlement and were actively associated with those in the field.

There was, therefore, little chance of farms bought for settlement remaining unsold.

However, in 1970, the British government decided to provide future land transfer funds on grant terms, and disassociated itself from the actual settlement.

This created a leeway for prominent people to acquire huge tracts at the expense of poor Kenyans.

SHIRIKA SYSTEM

About that time, the Jomo Kenyatta administration introduced the Shirika system of settlement. This involved a farm being bought from a settler and run by the Settlement Fund Trustee (SFT) as one unit.

A professional manager was then put on the farm and the settler given a small plot for his house on the same piece.

In theory, the settler also provided the labour to run the farm under the manager’s direction.

In November 1974, the British government started receiving rumours that farms bought using its funds were being sold to senior State officials.

These rumours mainly came from British civil servants attached to the Ministry of Lands and Settlement.

Dermott Kydd, a British valuer seconded to the ministry, secretly forwarded to his government files and a list of farms allocated to prominent individuals.

Among them was LR 8668 – bought using the settlement fund but sold to Kimo Ltd, which was linked to Cabinet Minister GG Kariuki.

A month later, Kydd had a run-in with Mzee Kenyatta over Sukari Ranch. The land in question was described as “a 30,000-acre ranch extending from Nairobi City boundaries in the general direction of Ruiru, Kahawa and Gatundu”.

VALUER SUMMONED

The land had been owned by French Scofin Company until early 1974. Since reports showed that the development of Nairobi would definitely cover a good deal of the area occupied by the ranch, a Cabinet paper was prepared suggesting that the government buys the land to prevent any speculation.

For reasons still unknown, the Cabinet failed to reach an agreement on its acquisition. Instead, Mzee Kenyatta is said to have bought it at Sh400,000 in March 1974.

Nine months later, the president expressed his intention to sell part of the ranch!

On December 17, 1974, Director of Settlement James Njenga phoned Kydd to inform him that the president wanted his ranch to be given an unseen value immediately so that he could be paid by the Settlement Fund.

Kydd refused to give a valuation until he saw the land. He also did not want to be involved in the transaction.

Kydd was summoned to State House on December 18, 1974. What followed is a story for another day.

The increasing reports of farms falling into the hands of well-connected individuals were becoming a concern to the British Ministry of Overseas Development.

BRITAIN RAISES CONCERN

In a February 3, 1975 letter, the ministry wrote to the High Commissioner in Nairobi, Sir Anthony Duff.

“We should be grateful if you would keep an eye on this. As Land Transfer Programme for settlement is entirely funded by the grant, we are bound to keep a serious view of this development,” the letter said.

Acting on these instructions, Sir Duff held a meeting with Ministry of Lands and Settlement Permanent Secretary N.S Kungu on March 25, 1975.

According to minutes of the meeting, he informed Kung’u that what was happening was contrary to the British government’s purpose of cooperating in the land transfer programme.

“The British government might well come under criticism in the UK if it seems to be acquiescing in the transfer of land to individuals instead of to landless Africans,” Sir Duff told Mr Kung’u .

The PS agreed with Sir Duff, saying there was a problem and the future was unpredictable “since instructions are coming from above”.

On April 17, 1975, Vice-President Moi, seemingly concerned about the misuse of British settlement funds, approached Sir Duff to complain.

According to a copy of the minutes of the meeting marked “Confidential, Reference…15”, he was worried that too many people in the government were acquiring farms “because of British generosity”.

MOI'S ADVICE

He had just confirmed to the British what they suspected.

Moi was particularly concerned about Barclay Farm in Menengai, which he said had been taken over by a group of individuals, “displacing those who ought to have it”.

The farm had been bought from Hugh Barclay using the settlement funds but later on sold to Mang’u Farmers Co-operative on the instructions of Mzee Kenyatta.

Duff had initially asked Njenga whether he knew members of the cooperative.

Njenga simply replied that it was a group of between 500 and 1,000, but he didn’t know if they owned other farms.

Nevertheless, Moi’s advice to the British was that they should temporarily suspend funds to the Department of Settlement.

Consequently, the British decided to withhold payments until the discrepancies were addressed.

They also set a condition that landless Africans were to be settled on farms first and a proof given before claims for payment were forwarded to London.

With the loopholes for irregular land acquisition getting sealed, Njenga banned British valuers attached to the Ministry of Lands from accessing farms earmarked for settlement.

OWNERS INTIMIDATED

That meant that without their own valuers, the British could not tell if landless Kenyans were being settled.

“Without these men dotted around the country, there will most definitely be misuse of our funds, and we shall be in no position to stop or detect it,” the British complained.

In some cases, people were placed on farms to masquerade as settled Kenyans, while in others, officials just did not care.

In a December 24, 1975 letter to John Kerr of Kitale, Lands and Settlement Minister Jackson Angaine said: “I am surprised to learn that you have changed your mind not to sell your farm in spite of your promise to me and my wife when we visited your farm.

“I asked my director of settlement to write a letter of intent to you so that you may be paid your money in the UK and then the SFT would transfer the farm to me which would make no difference to me. You are an old man whom I respect very much, and I could not think if such a gentleman as you are would twist me like that. I am coming to see you on January 6, 1976 at 10am for further discussions.”

The writer is a journalist based in London