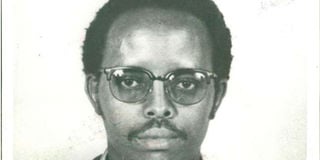

Hos Maina: Photojournalist who told the story with verve and valour

The late Hos Maina who worked for Nation Media Group as a photographer before moving to Reuters. Quick to act and with an eye to detail, the late Nation journalist did not confine his photography to football or even sport. His eyes were wherever good pictures were. PHOTO | FILE

What you need to know:

- But on that day, Hos brought me two things: the contact sheet and one print which he had gone ahead to produce without my authority

- To the best of my knowledge, this was the picture that changed sports photojournalism in Kenya. Before it, the word action picture always denoted action on the pitch, in the court, or in the pool

- I spoke for Hos’ family during his funeral mass. But I could never do it as well as Jonathan Clayton, his boss at Reuters

Twenty five years ago, one of Kenya’s greatest photojournalists died. His violent death in the line of duty propelled him into the pantheon of journalism’s martyrs and his tragedy was covered extensively throughout the world. He had started his career as a photographer for Nation Sport.

On this Mashujaa Day, I remember him.

I was the sub-editor on duty at the Nation Sports Desk one Sunday evening in 1981 or 82. Reports of league matches were streaming in from stadiums across the country. The big match of the day in Nairobi was a Kenya Breweries versus AFC Leopards game.

The photographer assigned to cover that match was Hos Maina. The practice in those pre-digital days was for the photographer to develop his roll of film in a darkroom and then produce a contact sheet of all the pictures he had taken. Then he would take them to the Editor to select the one he thought would complement the story.

But on that day, Hos brought me two things: the contact sheet and one print which he had gone ahead to produce without my authority. I looked at the picture for a while, with widening eyes and a breaking smile. It wasn’t necessary to ask him why he had breached the rules, the photo spoke volumes.

It was a black and white close-up shot of the AFC Leopards technical bench with Coach Robert Kiberu in the middle. The men’s eyes were frozen as he focused on the action. Some hands were held out, others supported their chins and others lay tensely on the laps.

Breweries versus Leopards matches were always hard-fought affairs and this picture was obviously taken at a particularly trying time for the cats. It was a picture that told many stories.

To the best of my knowledge, this was the picture that changed sports photojournalism in Kenya. Before it, the word action picture always denoted action on the pitch, in the court, or in the pool.

Hos Maina changed all that. He showed that an action picture could depict no motion at all. And it could, as Harold Evans, once the Editor of the London Times said, be a moment frozen in time that “preserves forever a finite fraction of the infinite time of the universe.”

“This is good, Hos,” I told him. “I want more like this.”

He smiled, his gamble having paid off. He had recently returned to Kenya from the United States and he looked at things differently.

He loved badminton and basketball, both of which he played. He used to bring me their match reports until I told him one day: “Hos, why don’t you drop sports reporting altogether and concentrate on photography? Your pictures are very good, but your copy is problematic.”

He asked simply: “You think so?”

“Yes,” I replied, unsure about how he would take that assessment.

“Ok,” he said. There wasn’t even a hint of disappointment. His career as a sports reporter ended there and one of the best photojournalists seen on these shores shifted his focus.

He brought me copies of the American magazine, Life and we thumbed through them with a voracious appetite, deciding which kind of pictures he would take. We would stare at some for long periods and return to them afterwards – for yet more studying.

Pictures of the expression on a spectator’s face or a coach’s reaction are now commonplace in the sports pages. But I remember how this revolution started because I happened to be in the middle of it.

Hos had first tried to get a job at the Standard Sports Desk. He went and spoke to a polite and helpful man called George Obiero, the Sports Editor. George didn’t have a place but he kindly referred Hos to the Nation Sports Desk.

When he came, he asked me whether I was Dick Agudah, who happened to be my boss. I wasn’t, I told him but how could I help him, since I was holding down fort in Dick’s absence.

That’s how our relationship started. It went on to the end of his life, encompassing our families in the course of its fifteen years.

Hos didn’t confine his photography to football, or even sports. His eyes were wherever good pictures were, including those of his own family.

This is one of the photos captured by Hos Maina during his time at Nation Media Group. Pat Neylan from Naivasha captured the Experts class in the 22 calibre competition after scoring 580 points in the 50 metres English match at the General Service Unit Training School. PHOTO | HOS MAINA |

But outstanding as he was, he struggled to get the attention of the bosses at the Nation. His break came in August 1982, during the attempted coup against President Daniel arap Moi’s government.

He was the only Nation photographer roaming the dangerous streets of Nairobi that day.

When rebel Air Force soldiers seized KBC, the country’s only broadcasting station then and announced that they had overthrown the government, mobs of looters invaded the city. They looted the shops and from fellow looters. The rebels helped them, sometimes shooting open pad locks.

There was no public or any other form transport and I never knew how Hos got himself to town. But I was with him throughout the mayhem, having walked from Kariobangi South to the city centre naively believing that my press pass would exempt me from the curfew that the rebels had declared.

Only seven of us had made it to work and when a thoroughly shaken Moi announced his own curfew, we found ourselves trapped in the building. But it was far from safe.

After loyal troops retook Broadcasting House around midday, they fanned into the streets, taking hundreds of lives, mainly university students and rebel airmen, with their rifles. Hardly any questions were asked. The city was a theatre of death.

Every now and then, we ventured outside the building but none of us was as brave as Hos.

He traversed the city carrying his camera inside a kiondo (traditional Kenyan bag carried by women) covered with sukuma wiki (kales).

Each time he saw a good shot, he pulled the camera out, snapped, and returned it to the kiondo.

When confronted by troops and looters, he said he was just looking for food for his family, as they could see for themselves. If he hadn’t been that resourceful, he most certainly would have lost his camera to the looters or been killed by the highly excitable soldiers.

We got marooned in old Nation House that night. We made do with sugarless black tea. Without cigarettes, those who smoked puffed at rolled up newspapers before they ran out of matches.

Save for those taken outside the central business district, all the pictures of the coup attempt in the Nation of August 3, 1982 were taken by Hos Maina.

From then on, there was no turning back. He took great sports pictures but he was now needed everywhere.

This is one of the photos captured by Hos Maina during his time at Nation Media Group. Gor Mahia forward Ben "Breakdance" Oloo (R.I.P.) vies for the ball with KTM's Hesbone Ndelwa during a past league match at the Thika Municipal Stadium. PHOTO | HOS MAINA |

In short order, he attracted the attention of the world media. Reuters, the international news agency, called for applicants to fill a vacancy in their Nairobi bureau.

Two friends, Hos Maina and Sam Ouma, were among the applicants. After the interviews, Sam, who would later become the Nation Photographic Editor, told me:

“I said to Hos, ‘I really need this job and so do you. Let’s pray, you for me and me for you. May the best man win. And with that we shook hands.”

Later, Reuters announced that it is Hos who had gotten the job. I was happy for him and we both wished each other good luck.”

The ending was one of the greatest tragedies to befall journalism in the world.

Hos and three colleagues, two from Reuters and one from the Associated Press, were separated from a convoy of media cars as they went to photograph a United Nations helicopter assault in Mogadishu, Somalia, on July 12, 1993.

They were stoned to death by a frenzied mob in that war-ravaged city.

He had gone there to bring their plight to the attention of the world. This would hopefully have led to help for them.

But in their consuming madness, they could not see this. And so they killed him. This resulted in their own loss and that of the world.

It would be years before any semblance of normalcy would return to their country – and a lot more Kenyan blood would sink in their soils. It is still sinking.

I spoke for Hos’ family during his funeral mass. But I could never do it as well as Jonathan Clayton, his boss at Reuters.

In Images of Conflict, a book published to celebrate the work and life of the fallen four in Mogadishu, Clayton summed up Hos Maina’s life with simplicity and profoundness:

“Hos nearly died in a car crash a little over three years ago,” he wrote. “A local Catholic priest read the last rites, but Hos fought back from the precipice of death, spurred on by the thought of his young family, to resume work a few months later. But it was to be a long, hard – and often thankless – road back.”

Gor Mahia's Tobias Ochola (left) beats Re-Union’s roving winger John Odie in a past league match at the Nairobi City Stadium. League leaders Gor won 2-0.

“Permanent injuries often left him depressed and frustrated that a job once so easy had become difficult. But never once did he think of quitting, only of ways to accelerate his return to peak performance. He spent hours learning new techniques to overcome the disability of a half paralysed right hand and examining ways to make the business of transmitting photographs easier for him to manage.”

“It is a dreadful irony that by the time of his death, he was shooting his best photographs for several years. During those last terrifying weeks in Mogadishu, he had won front pages on newspapers across the world and much praise from the London picture desk. He was immensely proud to be back at the top of his profession. In that way, at least, he died a happy man.”

I hoped so. In a family gathering, we once asked him what drove him. He replied: “I see the world through the lenses of my camera.” He was created fit for purpose and not even that near fatal accident could stop him. He froze some of Kenya sports’ greatest moments and his place in our profession is assured. He is a hero.